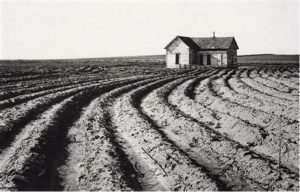

‘Tractors replace not only mules but people. They cultivate to the very door of the houses of those whom they replace.’ Dorothea Lange and Paul S Taylor An American Exodus. A record of human erosion, 1939

The discourse about our current NHS problems often reduces these to notions and language better suited to manufacturing, commodities and utilities than to complex human bonds and interactions. What has happened? Why? And what can we do about it?

Technology made large populations possible; large populations make technology indispensable.

Joseph Wood Krutch (1958), Human Nature and the Human Condition

August 2024

Several weeks after a landslide General Election result. For a while the combative sectarian rhetoric is quietened, as the vanquished – abject and bewildered – tend their wounds. Yet at the starting point of this staged battle there was always an anchoring agreement – some shared assumptions of what is and what should be. All parties agree, for example, that our NHS is floundering and in urgent need of bolstering; all similarly promised, for example, a rejuvenating increase in both staffing and its operational efficiency.

Of course, there had to be disagreements. The outgoing, now disarrayed, governing party said it has done these things and would continue to do so: it justified the evidently poor results on uncontrollable factors – the pandemic, subsequent healthcarers’ strikes and the world economy, for example. The opposition – now governing – party denied this: our problems are due, rather, to neglectful and nepotistic incompetence. They promise that their putative extra resources will be managed with more caring conviction, competence and probity.

The new government, so decisively victorious, now has its chance …

Despite this political sea change there remains another kind of agreement, but it is expediently befogged and stealthily dissembled by all: it is about funding. Where will the money come from? ‘Economic growth’ seems a capricious promise. Yet all major parties avoid saying: ‘We are all now expecting lives to be enhanced, largely ensured, and often usefully lengthened, by our continually advancing technology. Yet such technological growth depends on more funding. If we want such blessings we must be prepared to pay for them – all but the poorest should be willing to pay more taxes…’

Many politicians may believe this but dare not say it: they think, or sense, that the electorate would (mostly) reject any such self-compromise that prioritises, instead, our communal predicaments and thus any longer-term realism. It is likely that a politician of greater candour or integrity would lose their seat and (limited) influence to those who expediently sidestep or deny such inconvenient truths.

It seems we are not yet ready to welcome increasing our progressive taxes to ensure and honour any expanding communal welfare.

Current limitations

There is yet another healthcare no man’s land where we stumble, purblind, amidst our perceived problems and juggling solutions – and it is quite as misguided and serious. It is signified by how, generally, we restrict our description, analysis and debate about our NHS healthcare. We confine ourselves to particular language, concepts and data – these are, almost always, about distribution of funding and resources, and then how these are ‘managed’. We talk of our healthcare as a commodity, a service industry, a utility – much less do we hear notions of relationship, motivation, resonance, belonging or community … the kind of complex humanity that motivates people to want to do these difficult jobs well, and to stay in them happily over a working lifetime.

Instead, almost all politicians, analysts, pundits and media-commentators confine their formulations to a necessary-but-not-sufficient service industry perspective. So almost all the public hears are charges or laments about current shortcomings of resources, or promises about what extra, in future, will be provided: GPs, specialists, nurses, scanners, drastically upgraded and integrated IT systems, new hospitals … Manna from a New Order!

Many of us detect a manic nervousness in such promises: unanswered questions of funding continue to rankle. But that is not the only, or even the major, area of neglected oversight. Even if we could rapidly provide all these professionals, facilities and commodities, we would still be left with some recently evolved yet fundamental deficits – the displacement and destruction of our vocational spirit and communities; the abandonment of those subtle and fragile personal meanings and connections that can make this work so worthwhile and endurable.

These are complex losses with enormous consequences. They have accrued incrementally largely amidst, and because of, the serial reforms that are – paradoxically – meant to bring us all benefits through industrial efficiency and commercial acumen. The technical and legal details of those reforms have escaped most people’s interest and understanding, but the resulting dissatisfactions from ‘Service Users’ and ‘Service Providers’ (sic) are frequently heard:

- ‘I never see the same doctor twice…’

- ‘They don’t know my story so have to spend their time looking on the computer instead of seeing me.’

- ‘I’m no longer looking after, or looking out for, patients I get to know well, nor do I do this with familiar colleagues who become like family … I may be called ‘Doctor’, but I feel like a factory worker in the service of a remote corporate employer.’

- ‘In the past I felt it was a private matter when and how I saw my doctor (GP); it was like an ongoing personal conversation that I largely decided – that now all seems managed by people I don’t know, or even computers…’

- ‘Yes, we’re now in this shiny new building, with automated and electronic-everything but somehow, with all that, the heart and joy have gone out of the work…’

Such refrains, from both patients and healthcarers, have become increasingly common and now, surely, tell us much about the more unspoken predicament of our healthcare.

It is this predicament – the advance of micromanaged systems at the expense of personally meaningful and gratifying relationships – thence some kind of experience of ‘community’ – that is so little recognised, understood or discussed in our public discourse …

The demise of continuity of care

The absence of these considerations – of personal relationships, meanings and communities – in our thinking, planning, management and then practice of healthcare now has insidiously destructive effects. These are certainly equal to the substantial damage from the much-discussed inadequacy of funding and physical resources.

The historical evidence for the importance of this is compelling. Prior to the 1990s (the beginning of neoliberal, then digital-mediated, systems reforms) the NHS was of very variable quality, (relatively) technologically primitive and often cumbersomely slow. But in many ways it functioned excellently. For example, staff morale and esprit de corps were generally much better than now: recruitment, retention, team-stability, delayed retirement … all indicated that practitioners liked their work. This was because they experienced what they did as people-work: they worked in smaller stable teams with both patients and colleagues they could get to know increasingly well. Rarely, if ever, did anyone talk about ‘contracts’.

This pre-serially-reformed NHS often provided personal continuity of care far more readily, particularly in primary and mental health sectors. Such personal continuity far exceeds mere niceties and comforts: wiser practitioners and managers recognised this (informally) as a sine qua non of their work. We have now massive evidence to show that its beneficial influence reaches far beyond well-documented staff morale, work satisfaction and stability, and patient trust and positive experience. Such personal investments and understandings are related to significantly better outcomes in chronic disease management, fewer specialist and emergency service referrals, less psychiatric breakdown and self-harm, and significantly increased longevity…1

So recognising the importance of people – having a personal understanding and sense of community with individuals – does not just help them feel better about one another and themselves: it saves money and resources. How come, then, that such recognitions have been allowed – even enjoined – to perish?

Those who choose a more political and sectarian political analysis often, and very plausibly, argue that these losses are primarily due to deliberate inadequate funding; and that, they say, is due to the regressive economic consequences of neoliberalism and its characteristic austerity policy; even worse is the nepotism (for the few) and the marketising dehumanisation (for the many) that such policies lead to. This, they say, is an inevitability of our unbalanced and unfettered capitalism.

Yet however cogent this view, it does not adequately account for why so many of us in the more industrialised (‘advanced’) countries are facing similar and wider problems of human-ecological imbalance – our ability to live together, and with other species, in ways that are humanly fulfilled, synergistic and sustainable. This raises all sorts of other questions. What kinds of increased economic growth, technological cybernation, mass production and consumerism are compatible with our viability and broader welfare? Which tasks are best depersonalised and delegated to machines and which not? Why, in this country, over several decades, have we increasingly modelled our healthcare (and other welfare services) on competitive and corporate manufacturing industries? Why do we think we can better our welfare services by everywhere ratcheting-up commissioning, regulation, standardisation, compliance and inspection?…

Such questions may include, yet far exceed, party politics – rather they signify symptoms and predicaments of our industrialised culture, our era: Zeitgeist.

Taking the longer view

As always, history may help us understand what has happened, what is happening now, and even what we might best do.

Here is a very wide and long-spanned view.

Recent human evolution has seen an astonishing acceleration of human power – our abilities to manipulate one another, other life forms and our physical environment. Homo sapiens has become Homo instrumentulans; conscious humankind has become, very emphatically, Man the Manipulator – increasingly we engineer our world. We command it according to our designs and desires. This is massively true of our physical environment; it is increasingly true, too, of our bodies … such control of our minds is proving more refractory.

Generally, though, we have privileged ourselves to treat the world as a gigantic, almost infinitely intricate machine that lies prostrate before us, merely awaiting our ‘understanding’ and control.

But this species’ self-empowerment comes with very great costs and responsibilities: our powerful engineering is almost always at the expense of other life-forms. Almost always, others are destroyed, displaced or mutated. Such collateral damage often becomes more unconscious with our increasing efficiency. It is, therefore, very hard indeed for engineering to exist without some form of near or distant ecocide. That is the cataclysmic dilemma, the ‘inconvenient truth’, the incomparably important lesson we are having to learn from in the twenty-first century.

It is as if we have built a diorama of this in our NHS: more and more we are treating this enormously complex network of human experiences and needs as if it is merely a machine that can be reductively designed and managed to perform better. So like, say, an internal combustion engine: can we improve the fuel flow or air intake? Increase the compression ratio? Optimise complete combustion? Have more sensors and electronic controls? Increase the Octane rating? Etc. The system is there to be driven to perform better for us…

Hence the talk of improving our services is so often analogous: ensure more funding (fuel); shorten the training (increase the compression ratio); tighten surveillance, regulation and compliance (engine management systems and sensors); recruit more staff from other (poorer) countries (subcontract cheaper essential components), and so forth. All are there to drive up performance.

This is largely how we talk and what we do. Increasingly we see our health service as an inanimate machine: its management a task of civic engineering.

And before this …?

A better past?

In the post-war decade, the era of the birth of the NHS, our powers of technology and cybernation were significantly less. Engineering had not yet so utterly displaced and then deracinated ecology. This enabled our services to function more akin to more complex living organisms, say mammals: it was tacitly recognised that they needed nourishment, protected space, relationships that stroked, groomed and recognised, and – in humans – provided meaning.

Because we did not then have the power to directly manipulate and engineer as we do now, we had, instead, to grow our working communities and institutions – much as a gardener tends plants, or parents raise families. Whatever the technological inefficiency of this pre-industrialised era, these were – in human and community terms – halcyon days. Older practitioners and patients felt they belonged, they mattered, and their individual stories, meanings and natures were more likely to be recognised. Such things are essential for any kind of effective and sustainable people-work. Affectional bonds are not an irrelevant epiphenomenon of such work – they are essential elements, a generating force.

All of this has been largely displaced, extinguished or eclipsed by our drive towards industrialised packing, coding and cybernation – the tools and systems that are so indispensable to our successful manufacturing industries are often subtly yet deeply inimical to our people-work.

This is, increasingly, what we cannot or will not see.

Technology rich, humanity poor

A recent example of this came from Wes Streeting in his first public statement as Secretary of State for Health in the new government. His demeanour and voice were stern, bullish and uncompromising. He said:

‘From today, the policy of this department is that the NHS is broken.

‘That is the experience of patients who are not receiving the care they deserve, and of the staff working in the NHS who can see that – despite giving their best – this is not good enough … [We have] received a mandate from millions of voters for change and reform of the NHS.’

The rhetoric here far exceeds any useful meaning. Saying the NHS is ‘broken’ does not help us understand or remedy its malfunction. For example, if we have a substantial problem with our car, say, and a motor mechanic deems it merely as ‘broken’, that cannot help us. All acknowledge now that the NHS is functioning poorly. Repeating this as a ‘policy’ makes for little sense or help. We have, instead, to accurately identify the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of the malfunction.

Similarly, to assert that the solution to the obscurely-defined ‘broken’ mandates ‘reform’ raises far more questions than answers. As we have seen, the serial reforms of the last thirty years – however well-intended – have generally rendered far more administrative than human sense. They have resembled elegant and impressive architects’ models of buildings that subsequent inhabitants do not want to live in. So it is, for example, that our radically reformed general practice has morphed from a stable and happy ‘family’ network of colleagues into an unhappy and fractious network of siloed factory employees in which few wish to work. The erstwhile family doctors mostly enjoyed their people-work and often were reluctant to retire; the current GPs – Primary Care Service Providers – do not like their de-peopled work. They consequently work part-time and are unlikely to work until retirement age. Most pre-reformed GPs invested their lives and skills in communities that had sentience and meaning for them; the current thoroughly-reformed GP is, by contrast, contracted, controlled and regulated – the commitment to investment in communities, with their shared growth of meaning and sentience, is now all but impossible.

Increasingly our doctors work in milieux that are technology-rich yet humanity-impoverished; scanner-sighted but humankind-blind.

A price too high?

Perhaps this predicament – this Zeitgeist-folly – is currently reflected in the evident and increasing disturbance and unhappiness in so many of our children and young people. They are now surrounded and infused by technologies that conjure unprecedented instant and remote contact, virtual networks and screen-imaged presence … yet so many young people now, simultaneously, show alarming signs of unattachment, non-belonging and estrangement from self and others. They seem to be adrift from real communities that provide meaning and motivation.

We – the supervising adults – the parents, the teachers, the healthcarers, the police, the coroners – are witness to the casualties of all this in its many forms. We have categories, of course: severe dysthymia with self-harm, eating disorders, autism, drug abuse, gender dysphoria, ADHD, dangerous violence (even homicide) … the list is growing.

From our initial enthusiasm – a couple of decades ago – and welcoming of providing our children with this wondrous techno-cornucopia we have slowly become sceptical … and now confused and alarmed.

As so often in our contemporary world, our cleverness so easily outruns our wisdom. We lose the discipline, the restraint, the discriminating judgement to ensure that impatient expedience does not become unmanageable excess. How do we steer appetite away from obesity, palliation from addiction?

And in healthcare how do we best garner the considerable power and efficiencies that our ever-advancing technologies bring us, while also retaining and nourishing our only-human and all-too-human bonds, understandings and communities?

There are no complete and final answers to this question.2 But avoiding it has a very high cost, in terms of both our health economy and our human experience.

We are paying that cost now…

Men reform a thing by removing a reality from it, then do not know what to do with the unreality that is left.

GK Chesterton (1928), Generally Speaking

Notes

- There is now an enormous amount of solid research demonstrating the many benefits of personal continuity of healthcare, especially in general practice. Perhaps the most comprehensive and long-term has come from a team at Exeter University, headed by Denis Pereira Gray.

See especially:

Pereira Gray, D et al. ‘Continuity of care with doctors – a matter of life and death? A systematic review of continuity of care and mortality’, BMJ Open, 2018

- Even attempting ‘good enough’ answers cannot be attempted here in an article of this length. However, interested readers might find some useful suggestions in Chapter 10 of Zigmond, D (2019), The Perils of Industrialised Healthcare, Centre for Welfare Reform.

Other recent non-systemic yet practical small-scale suggestions to restore a sense of community, belonging and social inclusion for junior hospital doctors have included the free provision of car parking, creches, cooked food in a designated dining area…

Such measures may provide some worthwhile palliation for a much more extensive problem.

David Zigmond

Executive Committee member, DFNHS

- Many articles exploring similar themes are available on David Zigmond’s Home Page

No comments yet.